By Robert Leiser and Harvey Kaplan

Robert Leiser, grandson of a German Jewish refugee, grew up in Dunfermline, and Harvey Kaplan is director and chairman of the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre.

Introduction

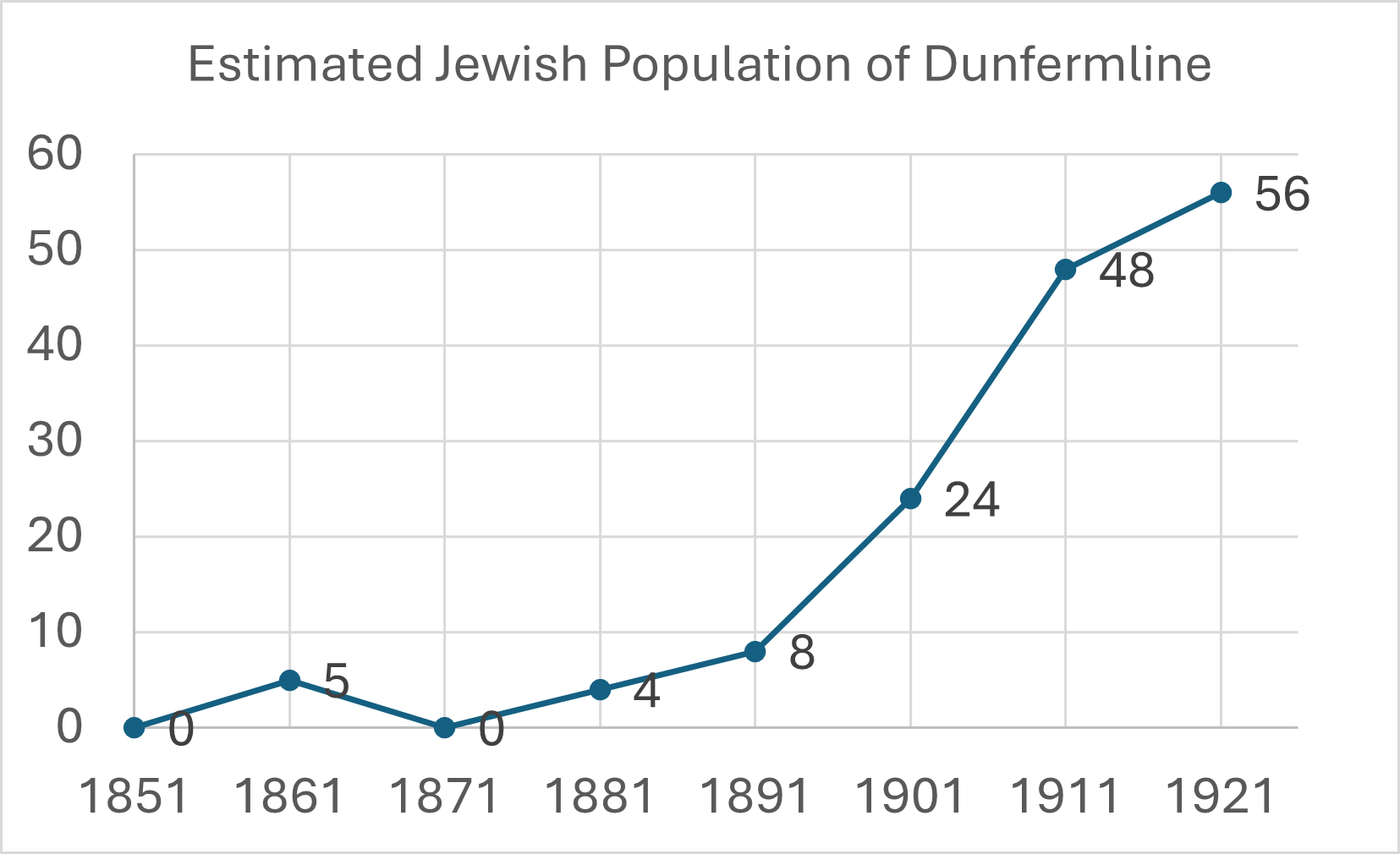

The first Jewish communities in Scotland were in Edinburgh in 1817 and Glasgow in 1821, but as more Jewish immigrants arrived throughout the 19th and early 20th century, small communities were established in Dundee, Aberdeen, Ayr, Dunfermline, Falkirk, Greenock and Inverness.

Using the records available at the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre (www.sjac.org.uk) and elsewhere, it is possible to learn more about the small Jewish community which once flourished in Dunfermline. Other sources of information on Jewish residents were in census records, birth, marriage and death certificates and newspaper accounts, as well as anecdotal evidence from and through local sources, such as Dunfermline Family History Group. As with any similar project, oral accounts had to be fact-checked, and a number of families and individuals widely believed to have been Jewish transpired to be Eastern European or German, but not Jewish.

First Jewish residents

With the growth of the linen industry and the expansion of the surrounding coal fields, Dunfermline prospered in the late 19th and early 20th century. Immigrant Jewish pedlars from Edinburgh, Dundee, Glasgow and elsewhere arrived in the town to sell their goods.

Jewish residents in the census

Early Jewish residents include jewellery pedlar Benjamin Alexander, his wife Rebecca and their three daughters, all dressmakers. Living in Reform Street in the 1861 census, they had previously lived in Cupar, but the parents had come to Scotland from Prussia. The 1881 census lists Polish-born jeweller Isadore Lyons, who had married Hannah Markinson, living in Netherton Broad Street. They had married in the town on 29 May 1880.

Some of the pedlars put down roots in the town and opened shops in the town centre.

Dunfermline Jewish Community

As the number of Jewish immigrants grew, a Jewish community seems to have been formed in 1908, with services taking place in New Row. Reverend S. Michelson was appointed as minister, a committee was elected, Hebrew classes introduced, and a Literary and Debating Society being formed.

Services later moved to Couston Street and Cross Wynd. By 1911 and 1921, the censuses show around 50 Jews living in Dunfermline. Reverend Morris Balanow was minister, shochet (ritual slaughterer) and teacher in the early 1920s. (His son Sholem, future minister of Netherlee & Clarkston Synagogue in Glasgow, was born in the town in 1921).

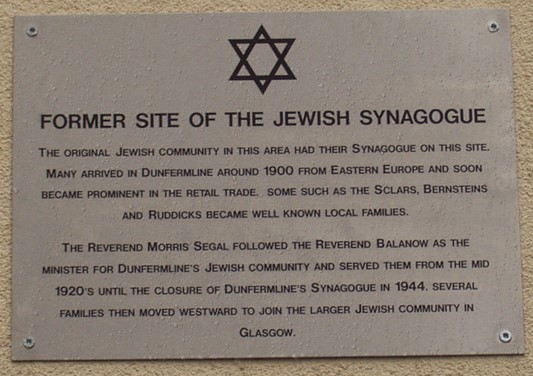

From the 1920s until the 1940s, there was a synagogue in Pittencrieff Street. Edith Ruddick, in her 1995 autobiography, ‘My Mother’s Daughter,’ remembered: ‘…The dozen or so families had their own synagogue, a small stone hall lined in yellow pine up an open wynd in Pittencrieff Street… it was built as a small sectarian religious meeting house, either by Seventh Day Adventists or Jehovah’s Witnesses…’

Kosher meat was available from a special department in Dunfermline Co-operative Society. In the 1930s, there was a Dunfermline Lady Zionists group. Rev. Balanow was succeeded in 1924 by Lithuanian-born Rev. Morris Symon Segal, who served until 1944.

Jewish families included Sclar, Brodsky, Miller, Bernstein, Segal, Ruddick, Green, Hodes, Warrens, Bloch and Rifkind.

Some of them had shops in the town, such as Bernsteins’ furniture shop, William Hodes’ antique shop and Minnie Berkley’s fashion clothing shop.

Acceptance

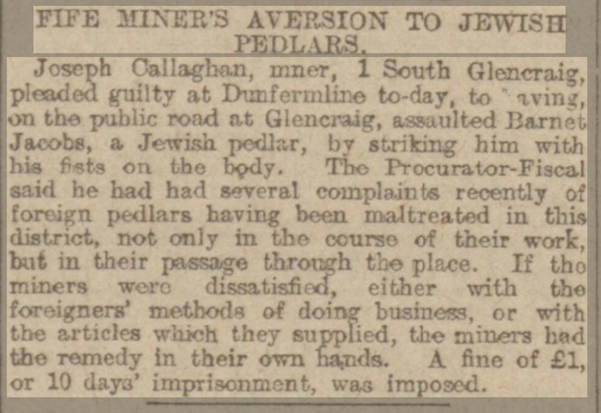

None of the former Jewish residents of Dunfermline reported issues with acceptance in the wider community. On the contrary, as described below, the service offered by Jewish traders was gratefully received, providing as it did a source of credit and access to goods not otherwise available. However, the Edinburgh Evening News of 2nd November 1908 reported a local miner being found guilty of assaulting Barnet

Jacobs, a Jewish pedlar.

The Fiscal’s remarks indicate that this was not an isolated incident, but the absence of similar reports suggests that such attacks were not widespread, and the fact that this crime was reported, prosecuted and punished indicate that this kind of behaviour was not generally accepted in society of that time.

Bernstein family

Amongst the thousands of Jewish immigrants who came to Scotland from Eastern Europe was Israel Brouda, who came to Scotland as a teenager about 1900 from Libau in Latvia. He changed his name to Bernstein and married fellow Latvian immigrant, Sarah Brandson, in Glasgow in 1905. They settled in Dunfermline, where in the 1920s, they opened a shop at 36 Chalmers Street, selling furniture, carpets

and menswear. They had three sons, Harry, Isaac and Sammy and Isaac also went into the business.

Another member of the Bernstein family was John Jacob Bernstein, who was a licensed broker and at one time a jeweller with a shop in Bruce Street. He became a Labour Councillor and Magistrate in Dunfermline around the First World War. About 1920, John emigrated to Australia, where he died in 1924.

Another descendant of the Bernstein family emigrated to Australia in 1972, returning for two years in 1974 and then permanently in December 1978. A member of this family still lives in the area today, the last local representative of Dunfermline’s former Jewish community.

Sclar family

Another prominent Jewish family in the area was the Sclar family. Isaac Sclar grew up in Cowdenbeath 1918-1975, and worked for and became chairman of electrical contractors James Scott and Co. in Dunfermline, as well as Secretary and Treasurer of Dunfermline Hebrew Congregation, 1920-1945. His sister Milly married Rev. Segal.

Berkley family

Harry Berkley was born Herbert Ellis Berkley Berkovitz in Glasgow in 1928, son of Hyman Berkovitz and Tilly Berman. He was brought up in the Dunfermline home of his aunt and uncle, Katie Berman and her husband Israel Miller, who had no children. Katie and Israel lived at 2 Athol Place, Dunfermline. The Millers were important figures in Dunfermline’s Jewish community and Athol Place is mentioned in various sources as the location of the town’s synagogue. In only a short street with very few addresses, it is probable that the Miller’s home served as the synagogue. Harry eventually took over Israel’s commercial traveller business. He travelled around the local mining villages with goods in a suitcase, offering items on credit, a very welcome facility for those communities. It was not unusual for households to have a jar on the mantlepiece known as “Harry’s Jar” containing the credit repayment cash due at his next visit. Harry’s wife, Minnie Berkley, had a shop in the town centre of Dunfermline, where she sold fashion clothing from warehouses in Glasgow. The Barmitzvah of their son is believed to have been the last to take place in Dunfermline.

Wartime

Like all over the country, the Jews of Dunfermline were caught up in the challenges and dislocation during the Second World War. Reverend Segal was an air raid warden and collected funds for the Red Cross. He and his family entertained visiting Jewish servicemen on sabbaths and festivals.

Julius Green was brought up in Dunfermline and joined the Medical Unit of the Edinburgh University Officer Training Corps. During the Second World War, he served in 152(Highland) Field Ambulance of the 51st Highland Division, but was captured in France in 1940. He was imprisoned in Colditz Castle, where he performed vital intelligence work for Britain.

Irene Hodes, from another Dunfermline Jewish family, was in the Civil Nursing Reserve.

Isaac and Doris Sclar fostered an 11-year old refugee girl, Dolly Mahler from Vienna. Dolly was born in Vienna in 1926, daughter of Adolf Mahler and Johanna (Hansi) Schwarz. In March 1939, the Mahlers decided to send their two children, Dolly and Friedl-Peter to England on a Kindertransport. They were accommodated with relatives in Manchester who had fled via Vienna to England in November 1939. Dolly later moved to Dunfermline, where she stayed with the Sclars.

In 1939, a small group of Czech and Sudeten refugees were housed in St. Ninian’s Retreat in the then mining village of Lassodie, 2-3 miles from Dunfermline. One of these refugees, Henry Kraut, married fellow refugee Gerda Fischer in Dunfermline in 1939. Others included Viktor, Lise and Kurt Fischer, Charlotte, Fritz and Hartmut Schild. It is not known which of these may have been Jewish, nor what became of them.

There was no dedicated Jewish cemetery in Dunfermline and community members were often buried in Edinburgh or Glasgow. However, 20-year old Harold Irving Chizy of Montreal in Canada, who was killed in action on board HMCS Nabob off North Cape, Norway, in August 1944, is buried in Douglas Bank cemetery in Dunfermline.

Mystery surrounds a grave in Inverkeithing Cemetery. William Newton was born in Inverkeithing in 1917 and died of lung disease at Hairmyres Hospital in 1942. He was a Royal Navy seaman based at the HMS Drake shore establishment. His Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) gravestone in Inverkeithing bears a Star of David, and CWGC documentation reveals that a cross originally ordered to mark the grave was cancelled, the grave being explicitly designated “Jewish”. The rigour on which the CWGC pride themselves makes it unlikely that this was a clerical error, but there are no indications in William’s family background that he or any other member was Jewish or had any affiliations with the Jewish community. Enquiries with surviving members of the family and the local community have failed to provide any explanation of this.

The end of the community

Most of the small Jewish communities in Scotland did not survive post-war, as young people moved to larger communities in Glasgow, Edinburgh, elsewhere in the UK and abroad. Others became less interested in formal Jewish observance and assimilated into the wider community.

After the war, Reverend Segal left for a post in Dundee. The community declined and services were moved to Athol Place (perhaps the home of Israel Miller, who lived at one time at 2 Athol Place). Orthodox Jewish services require a quorum of ten males and although some Jewish people continued to live in the town, the quorum was no longer viable, so the community was formally wound up by 1950.

Segal Place

In 2005, thanks to the efforts of a member of the local council, a new housing complex in the former synagogue area was named after Reverend Segal – Segal Place. It was named at an event attended by a number of people whose families had once been part of the Jewish community in Dunfermline. The plaque was unveiled by Rev. Segal’s son, Philip Segal and ensures that the memory of the former Jewish community remains in Dunfermline.

The Scottish Jewish Archives Centre preserves the records of the Jewish experience in Scotland, including Dunfermline – see www.sjac.org.uk. A list of material about Dunfermline in the Archives Centre collection can be accessed online at: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/4b194511-a92e-32d7-af44015db2087834

Conclusion

There is currently a temporary exhibition at the Scottish Jewish Heritage Centre in Garnethill Synagogue, Glasgow, about the former small Jewish communities in Scotland, including a section on Dunfermline (contact info@sjhc.org.uk). In addition, the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre would be delighted to receive further information, photographs and documents which shed light on the history and contribution of Jewish people in Dunfermline (info@sjac.org.uk).