A few years ago the Graveyard Group of Dunfermline Heritage Community Projects spent many happy hours recording all the gravestones in the Abbey churchyard and then went on to uncover some more that had become buried over the years. The results of our project are available as two databases in the Graveyard section of the dunfermlineheritage.org website.

Anyone who spends time looking at old gravestones probably thinks at some point. “I wish I knew more about that person”, so here are the results of research into the lives of some of the people who are buried in the graveyard. This article is based on a Twilight Talk given in September 2019 at the Carnegie Library.

There is a lot more to the history of Dunfermline than the linen industry and the mining that have been so thoroughly researched and written about, so here is an introduction to a few Dunfermline people who did other things. One of them was connected with the linen trade but you’ll also meet a merchant’s wife, a pauper, a missionary, a blacksmith, a baker, and a rags to respectability story.

The Merchant’s Wife

We begin with the earliest dated gravestone in the Old Ground, to the north of the church. It is dated 1625 and it lies immediately in front of the entrance to the Abbey Church. If the disabled access that is planned for this area is ever built this stone will have to be moved and the obvious place for it is in the Old Nave, with an information board giving the story you are about to read.

HIER LYES BARBARA STEWART SPOVSE OF IOHN LAW

MERCHAND AND GILDBRETHIR

IN THIS TOVNE

QHA DIED THE 3 IVNE 1625

HIR AIGE 77

THY QUALITIES TO COMPREHEND

THY HALIE CONVERSATIONE

THY GODLY LYFE THY BLISSED END

HEIR NOV SEALS THY SALVATIONE

This picture was taken after the stone was cleaned up – it is now mossed over again, which helps to protect it from weathering. The style is typical of an early 17th century stone – a wide border with a central panel and chunky lettering, like the text on the lintel of the Abbot House doorway. The text in black is a transcript of the border inscription and the text in red is from the central panel.

Barbara was an uncommon name in Dunfermline at the time, which made it easier to follow her life story – if she had been called Janet, for instance, it would have been much more difficult. She was born in 1548, so she would have been baptised as a Catholic, and she was 12 at the time of the Reformation of 1560 that established the Presbyterian church in Scotland. She may have even witnessed the altars and effigies from the Abbey being burned in the churchyard by the Lords of the Congregation.

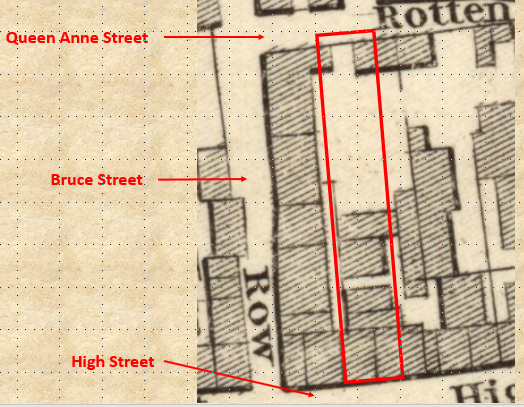

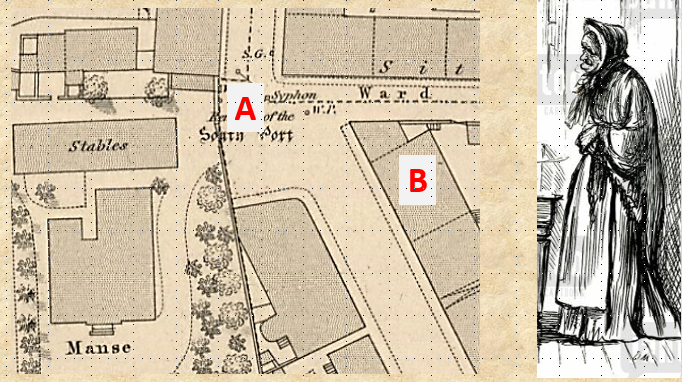

Barbara Stewart and John Law were married in June 1570 and their first child, Andrew was born the following year and over the next 20 years they had at least 8 more children. They lived in the High Street two doors east of what’s now Bruce Street – I have marked it on the plan of Dunfermline made in 1823. There was a dwelling house and probably a shop on the High Street frontage and the property went right back to Rotten Row, which is now Queen Anne Street, with a malt barn at the top end. Until about the mid-18th century Dunfermline was a very rural town and many of the burgesses ran small farms.

John Law became a member of the Dunfermline Guildry in 1587. Barbara’s father had been a member of the Guild and John Law entered it as the husband of a deceased member’s daughter. He had died by 1607, when his sons Andrew and Peter were made burgesses and entered the Guildry. In 1618 Andrew was elected Dean of Guild, but he had died by 1622 and Peter Law had become head of the family. It was probably Peter who had the expensive gravestone laid over his parents’ remains after his mother died.

Barbara and Peter survived a terrible famine after a crop failure in 1622. In that year the number of burials in the Dunfermline graveyard shot up to 120 from an average of about 40, and in 1623 they were even higher at over 400, about a quarter of the population. The town had barely recovered from the famine when it was hit by the fire of May 1624 that badly damaged many of the buildings in and around the High Street. Barbara died the year after the fire.

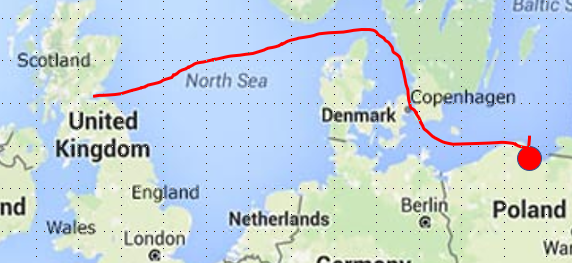

Peter Law was one of several Dunfermline merchants who traded directly with Danzig (Gdansk) in Poland, buying and importing lint and iron until the 1624 fire brought the trade to an abrupt end. He was Dean of Guild almost continuously between 1626 and 1634 and he served several terms as a bailie and was Provost from 1637 to 1640 and again in 1647. Peter died in 1656, in the middle of the Cromwellian occupation of Scotland, and his property descended to his son Patrick, but. Patrick was well-established as a dyer in Elie and had married an Elie girl, so he sold all his Dunfermline property, including the family grave plot. His seat in the church was bought by a merchant, Robert Douglas, and a grave plot was usually included in the deal, so it probably came to the Douglas family at that point. Part of the border inscription on the gravestone has been scrubbed off and the initials RD substituted.

The Pauper

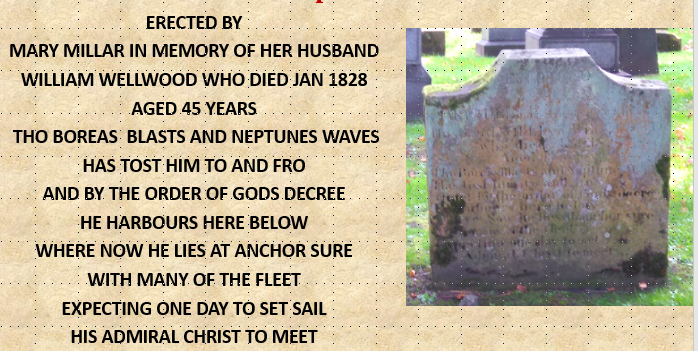

This is the story of how an Irish woman called Agnes Millar ended up living in Dunfermline under the name of Granny Wallet. The stone that marks her burial place (above) does not mention her at all, as you can see from the inscription. It is the gravestone of William Wellwood a shoemaker who seems at one time to have been to sea and it may have been on a voyage to Ireland that he met Agnes’ daughter Mary Millar, who was born at Downpatrick in County Down in 1791. By 1827 the couple had settled in Dunfermline, where their only child, Robert, was born a year before his father died.

The 1841 Census introduces us to Agnes, who had come to Dunfermline with her daughter and been absorbed into the Wellwood family (Wellwood was locally pronounced Wallet, as it had been since at least the 16th century). She was running a lodging house in the Netherton with her daughter and a new son-in-law, Craig McLean, a Glaswegian tailor. Her grandson Robert was living in the house and there were six lodgers, most of them Irish. There were several lodging houses in the town at the time and most of the people who ran them were Irish.

However, Agnes had another string to her bow. The Dunfermline reminiscences called When We Were Boys, tells us that children who did small tasks for the weavers were sometimes given handfuls of ‘ravellings’. On Saturdays ‘kindly old Grannie Wallet’ sat near the Manse gate (A on the map on the previous page) with a basket at her feet, into which the children put the ravellings and in return were given small cheap toys, balls, balloons or windmills. Ravellings seem to have been lengths of waste yarn but I have no idea what Granny Wallet did with them. The picture next to the map is a drawing of a poor Irish woman, which may give an idea of what Granny Wallet looked like.

It‘s an interesting thought that Andrew Carnegie, born in 1835 in a cottage directly opposite the Manse, (B on the map) was probably familiar with Granny Wallet and may even have owned one of her toys.

Grannie’s efforts to support herself were ultimately unsuccessful and in about 1845 she was taken into the Dunfermline Poorhouse, the first part of the building that is now the Leys Park Care Home.

There was a subtle difference between the Scottish poorhouse and the English workhouse. A workhouse was intended to be a deterrent to ‘spongers’. The regime was harsh, the food poor and the work unpleasant. The Scottish poorhouse, on the other hand, was intended as a refuge for the poor who could genuinely no longer support themselves.

At Dunfermline the regime was strict but reasonable – inmates who behaved well and could be trusted not to head for the nearest pub were allowed out, some of them even for holidays of a week or more. The food was plain but adequate and the work was usually a continuation of the jobs the inmates would have done in their own homes. The women did the laundry, cleaned the building, knitted and sewed. The men grew potatoes in the grounds, looked after the pigs and did small labouring tasks. Those who had been weavers were sometimes employed to set up looms. This is not to pretend that the life was idyllic, and there was still a stigma attached to being sent to the poorhouse, but the motivation behind the regime was benevolent, even though the inmates probably failed to appreciate that fact.

In spite of her life of poverty and hardship Granny Wallet lived to be 100 years old, and her death merited an article in the Dunfermline News section of The Fife Herald of 20 May 1847.

A few days ago one of the inmates of our Poors-house died at the very advanced age of 100 years and 3 months. Here name was Widow Millar, originally from Ireland and better known in the town as old granny Wallet (Wellwood). She possessed all her faculties except her hearing, which was a little imperfect, till within a few days of her death. She died of no particular disease, except that which Dr Johnson complained of as quite incurable, extreme old age.

The great age of this person is a striking proof of the benefits of a well conducted Poors-house. When she first became an inmate she was in the extreme of poverty, want and filthiness, but under regular diet and proper attention she speedily recruited and her constitution, originally of capital stuff, having rallied, she became a cheerful and canty auld wife as long as she was able to go about the house. We may reckon ourselves fortunate in having as governor and matron of our Poors-house, two such attentive and judicious persons as Mr and Mrs Monteith.

Most people who died in the Poorhouse were buried in one of the two ‘free’ areas of the New Ground (south of the church and identifiable by their lack of gravestones), but Granny would have been laid to rest in the Wellwood grave plot, on the east side of the path from the Maygate to the porch of the Old Nave.

The Manufacturer

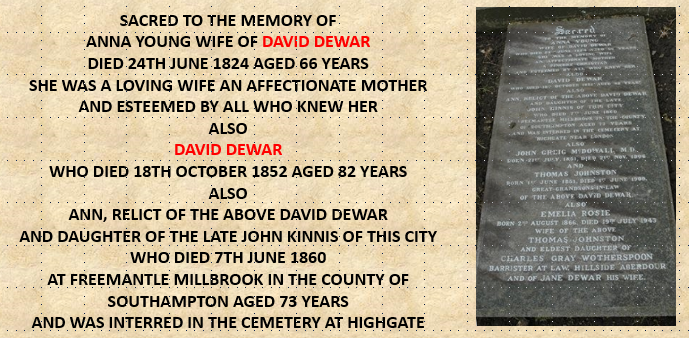

In 19th century Dunfermline the word ‘manufacturer’ meant a manufacturer of linen. David Dewar was one of the more important employers of handloom weavers and Dewar Street is named after him.

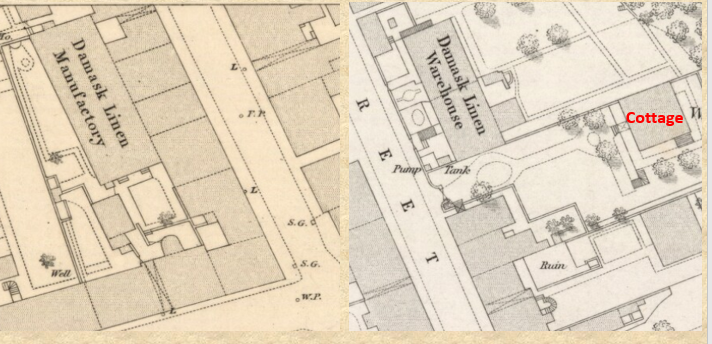

Here is David with his second wife Ann Kinnis. Her brother William Kinnis was at one time a business partner with David Dewar and was provost from 1839 to 1843. They were married in 1827, by which time David was well-established as a linen manufacturer. He was a very devout man, one of the first members of the Dunfermline Young Men’s Religious Society, founded in 1800. He was also a pastor in the Dunfermline Baptist church and was well-known for his benevolence to the poor. He supported the Temperance movement and the abolition of the Corn Laws that kept the price of bread high and his politics were firmly of the Liberal party.

Daniel Thomson, a local journalist knew David Dewar in his youth and this is what he had to say about him:

He was a low, slow-spoken but kindly old man when I knew him. He was very fond of children and would romp with them as far as he was able. He tried to promote the social and educational welfare of the young. In old age he was heavy and red-faced, slow-moving and slow-speaking but ‘though his voice grated on the ear it seemed always to find a response in the heart. ….He belonged to the small but excellent class of men who are willing to do even the small deeds of life if big ones cannot be reached…. Many of the poor were helped by him with advice, influence and money. He always held a feast for the poor on Handsel Monday

Another author, Alexander Stewart (Reminiscences of Dunfermline) also remembered David Dewar.

He was open-handed and generous and it was usual for him to have a large boilerful of broth, beef etc made ready on Auld Hansel Monday, that all the poor around the neighbourhood might have the comfort of a good, warm and substantial dinner that day. It was also his custom to assist in the culinary operations himself on those occasions and there he was to be seen with his bluff, honest face and in his shirtsleeves, working away, the picture of happiness and contentment. After all, there is much wisdom in the remark that “a true man is just as much a man when his coat is off as when it is on”.

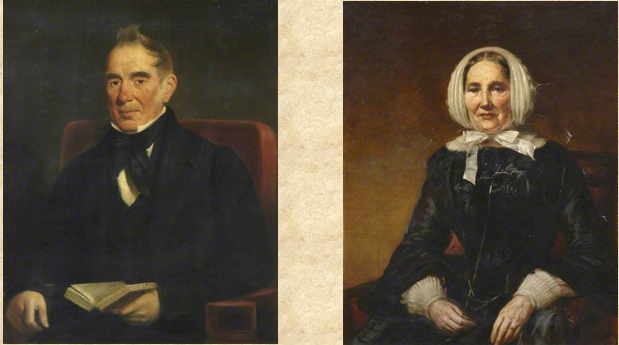

In 1840 David Dewar built the first handloom linen factory in Dunfermline. It was on the west side of Woodhead Street (now the northern half of Chalmers Street) near the corner with Pittencrieff Street and it housed 50 looms on three floors. At about the same time as the factory was built, David Dewar and William Kinnis introduced a new weaving process that produced fabric of three colours.

His warehouse was on the other side of the street. As so often happens with OS maps the join comes in a very inconvenient place and I have had to use sections from two sheets of the 1854 plan of Dunfermline. David’s house, Woodside Cottage, was near his Warehouse. It no longer exists but the small white chapel on the east side of Chalmers Street was built in its grounds.

The early years of David’s factory operation unfortunately coincided with the general trade slump of the 1840s. By the end of 1842 all the weavers in the town were working on short time, but David Dewar was the last employer to cut hours. He was also the first to revert to full time in the following March.

According to the 1851 Census he was then manufacturing woven carpets and table covers and employing 92 men, 8 women and 8 boys. That, of course, was the year of the Great Exhibition in London and David Dewar was one of several Dunfermline manufacturers who sent goods to be shown and this is what the Dunfermline Journal had to say about them.

The Messrs Dewar and Sons have forwarded to the Exhibition some table-covers in a new and gorgeous style, far superior to anything we have hitherto seen in brilliancy and elegance of design one of them four colours in silk and wool and the fabric in finish and texture is equal to the finest Saxony broadcloth.

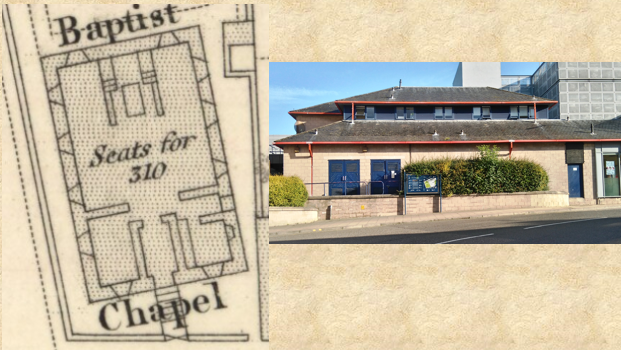

David Dewar was instrumental in getting a Baptist chapel built in James Street. Here it is on the 1854 OS Map and next to the plan is a picture of the building that is on the site now.

David died in October 1852 and his inventory lists the goods at his London warehouse – cotton table covers, worsted and cotton covers, crumb cloths (spread over the carpet under the dining table) and huckaback cloth worth just over £5000. These are all fairly coarse fabrics, a reminder that although Dunfermline became known for producing fine damask table linen, in the early days of the 19th century this was only one branch of a very varied fabric industry in the town. As we have seen, David also produced fabrics in wool and silk and in 1851 he had also been producing woven carpets.

His son James built a large power loom factory in Elgin Street (The Bothwell Works) in 1863, on the site now occupied by the TA and the Fife Council Environmental Services Depot. The large house on the north side of the top of Elgin street was the Works’ Office. James died in 1867 and the Bothwell Works was acquired by William Matthewson, head of the firm of James Matthewson and Son.

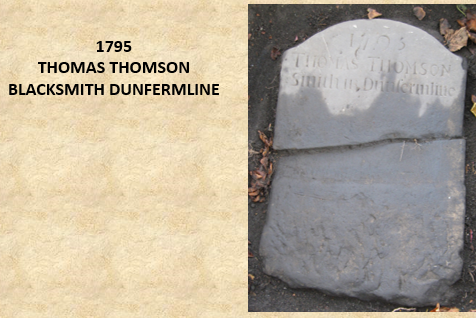

The Blacksmith

Now we move on to a man who would have been a familiar figure to both Granny Wallet and David Dewar – a blacksmith who was known as Tam Thomson. His gravestone is one of the ones we uncovered in our 2014 dig, and from the picture you will see that it only contained his name, Thomas Thomson, his trade and the date 1795, which was when he bought the plot. If that is all the information a gravestone contains, then the date on it is almost certainly the year the owner either bought the plot or put up the marker stone, not the date of their death.

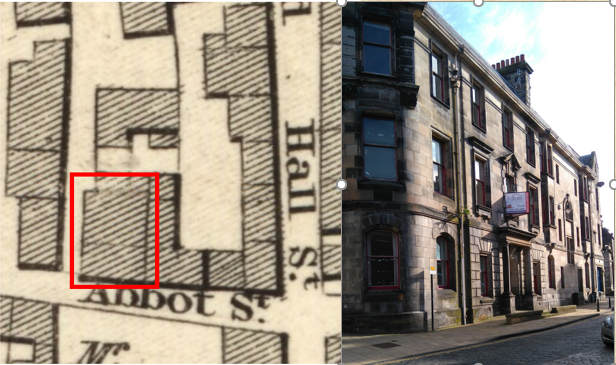

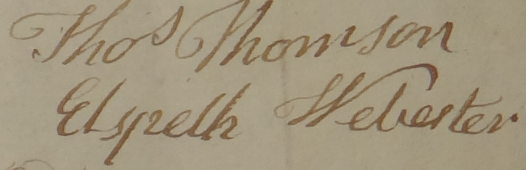

Tam’s father, William Thomson was a smith at Easter Gellet and Tam was entered to the Dunfermline Society of Hammermen in 1775. In 1781 he married Elspeth Webster and in 1785 they bought part of a yard on the corner of Abbot Street and the close now called Music Hall Lane. Here it is on the plan of Dunfermline made in 1823 and next to the plan is the building that is on the site now – the old Registry Office. There Tam built a smith’s shop and a four-roomed dwelling house.

By 1799 it was clear that the couple were not going to have any children so they had a legal document drawn up leaving all their property to each other. These are their signatures on the agreement.

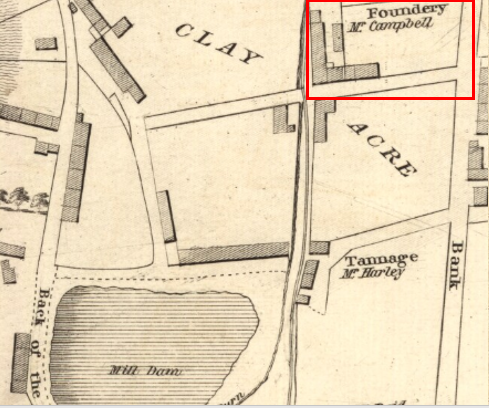

In 1815 Robert Campbell joined Tam in his smith’s shop and started a small foundry there. The following year Campbell moved to Clayacres on the north side of the town and set up The Dunfermline Foundry, employing 15 men. The street where it stood was soon being called Foundry Street, as it still is. Here is the foundry on the 1823 plan of Dunfermline. The Mill Dam on the plan is where the latest Tesco store now stands.

Tam Thomson died in 1831 and in 1834 his widow Elspeth sold the smithy and house to Tam’s nephew John Bonnar, who had been one of the builders of the new Abbey church in 1818 – 23. She stipulated that she was to live in the house for the rest of her life.

John Bonnar kept a kindly eye on Elspeth and in January 1845 he reported to the Parochial Board, who looked after the poor, that she was in very indigent circumstances, and offered to pay 2s a week towards her keep if she could be admitted to the Poorhouse (the average cost of keeping an inmate in the Poorhouse was about 7 or 8 shillings a week. Elspeth entered the House in the February and died there ten months later at the age of 97.

The Abbot Street property remained with the Bonnar family until 1902, when it was sold to the landlord of the Star Tavern. Eventually the site was swallowed up in the building of the Registry Office and I am very grateful to my friend Ian Ross, who gave me copies of his JPGs of the deeds of the Registry Office, which included the information about Tam Thomson’s smithy and house.

The Missionary

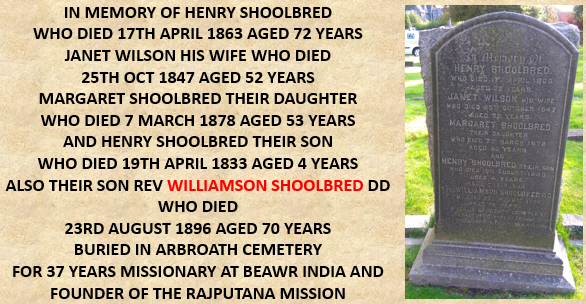

The relevant name on this inscription is Williamson Shoolbred. As you can see he was not actually buried in the graveyard, although he did own a grave plot in another part of it. But he was a native of Dunfermline, his formative years were spent here and he was only buried at Arbroath because he was on a visit there when he died, so he gets in on those criteria

Williamson’s religious background was a crucial influence on the way his life developed. His family were very devout members of what was known then as the Associate Congregation – now the Erskine church. His father Henry Shoolbred and all his aunts and uncles had been baptised at an Erskine church in Auchtermuchty and Henry later became a long-serving elder in the Erskine church in Dunfermline.

When Williamson’s grandfather John Shoolbred died he left legacies to his family and he had included this clause in his will

Now my dear wife and children, I entreat you to be agreeable. The advice Joseph gave to his brethren I give to you, “See you fall not out by the way”. Be agreeable as Christian brethren. I have settled to you the wonderful bounty of providence to me.

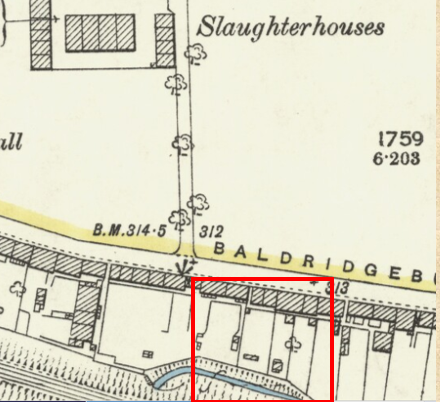

The Shoolbred family home was in Baldridgeburn, near the road that later led to the Slaughterhouse (built in 1863) and their garden backed onto the Baldridge Burn. There was no slaughterhouse in Williamson Shoolbred’s time but this map (1893) shows it and the red square marks the area where the Shoolbred house would have been. The road to the Slaughterhouse is now called Millar Road, but in the Shoolbreds’ time it was known as the Coal Road because it led directly to the Wellwood Colliery.

Williamson’s father, Henry Shoolbred, and his uncle James trained as weavers – at one time they worked for James and Robert Kerr whose business was on the west side of Bruce Street on the corner with Bridge Street. The Kerr brothers introduced the Jacquard weaving machine to Dunfermline in 1825 and James Kerr was the benefactor who paid for the land where the Public Park was laid out in 1863.

In 1817 Henry Shoolbred married Janet Wilson, whose uncle William Williamson ran a grocer’s shop near the Shoolbred’s house in Baldridgeburn. The Williamson connection was important to the couple and our Williamson Shoolbred was named after his great uncle, who was a witness at his baptism in 1827. By the time Williamson was born his father was running a loomshop and was described as a linen manufacturer. Henry’s brother James had built a weaving factory in Pittencrieff Street just round the corner from David Dewar. It held about 30 looms and James Shoolbred was one of the major handloom linen manufacturers of his time.

Great-uncle William Williamson, had no children of his own and he took a keen interest in his namesake nephew. When he died in 1843 he left him all his household furniture and two of the three properties he owned in Baldridgeburn.

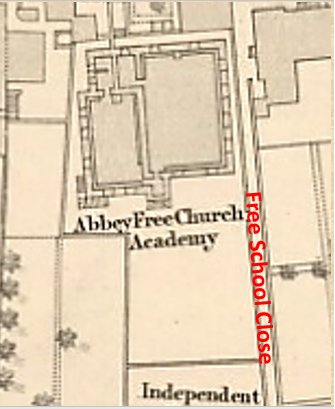

From the age of five until he was about thirteen Williamson attended the Free Abbey Academy, in what is now called Free School Close. After leaving school he went into business for several years (probably helping to run the grocer’s shop) but he continued to study under John Young, the minister at the Erskine church. In 1849 (aged 22) he entered Edinburgh University where he turned out to be a brilliant scholar.

One of his fellow students later wrote that ‘he was unquestionably the first man of our year – a good classic, a very able mathematician, circumspect in metaphysics and long-sighted in science’. After graduation Williamson also studied at Halle and Heidelberg and in 1857 he travelled in Egypt and the Holy Land. In 1858, now in his early 30s, he was licenced to preach and in 1859 he was ordained as a minister at the Erskine church, specifically to go out to India to found the first United Presbyterian mission at Rajputana, in the Behar province.

Missionaries usually came home on furlough from time to time and Williamson was back in Scotland by October 1869, when he addressed a meeting at a church in Aberdeen, and in January 1870 he married Catherine Allan, the daughter of an Arbroath solicitor. Their eldest son Henry was born in India in 1872 but by May 1878, when Williamson addressed a meeting in Edinburgh, they were back in Scotland. Williamson spoke at various meetings during 1879 and his second son, John Allan Anderson, was born in Edinburgh in 1880.

The mission founded by Williamson in India at was by now well-established and he continued to work there until 1895, when he contracted ‘hill fever’ and was ordered home. He and his wife stayed a short while with relatives in London and Dunfermline and then travelled to Arbroath to the house of his wife’s sister, where he died a fortnight later and that is how he came to be buried in Arbroath churchyard.

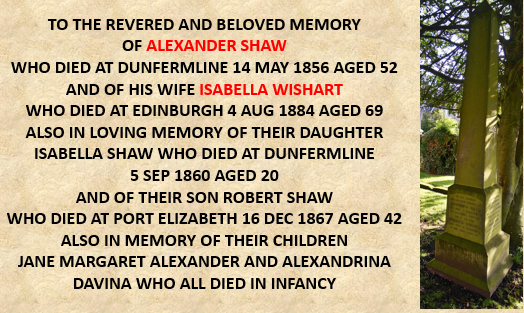

The Baker

Now we move on to a very different story. Unfortunately the obelisk gravestone is in the shadow of a tree so it is difficult to photograph but the inscription is very clear. Alexander Shaw was a baker who died comparatively young and his widow, Isabella Wishart, carried on the business for many years.

Victorian women were supposed to be timid shrinking violets who let their menfolk run their lives – that was the propaganda spread by wishful-thinking males. Life would be perfect if only all women knew their place. To test the notion that propaganda provides us with the truth, consider some of the modern propaganda about women. Is every woman you know yearning to become the head of a major company? There are shrinking violets in every generation but a lot of Victorian women were not at all like that, and Isabella Wishart is one example.

Isabella and Alexander were married in 1839. At that time the Shaw bakery was in the Maygate. By 1841 they had moved to Bruce Street and by 1851 they had come to rest in the High Street. Alexander, by the way, was the first baker to supply bread to the Poorhouse when it opened in 1843 and he often gained the contract in the following years. He charged between 5¼d and 7¾d a dozen for 6 oz loaves and, 8 oz loaves were 7¾d to 8d a dozen.

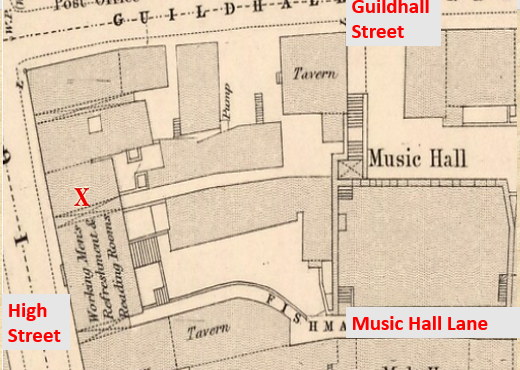

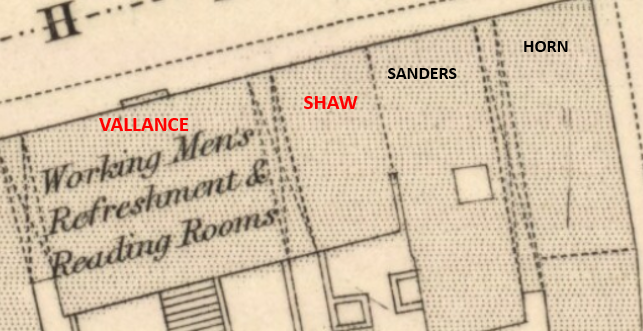

This is where the bakery was in the High Street, about midway between Guildhall Street and Music Hall Lane. (In 1854 when this map was published the lane was called Fishmarket Close.)

The four properties between Guildhall Street and Fishmarket Close all belonged to women. The one on the corner of Guildhall St (now the Santander bank) was a grocery shop belonging to Agnes Horn, widow of a linen manufacturer. The next one belonged to Helen Finlayson, who had established a confectionery business there by the 1820s. In 1850 she retired to keep house for her widowed brother in law Ebenezer Graham and let the premises to her former apprentice John Sanders, who bought it after Helen’s death. The property on the other side of the Shaw bakery belonged to Ann Vallance, an Army officer’s widow who ran a bakehouse and grocery. She let the first floor to James Dick who established a refreshment room in it and later turned it into a Temperance Hotel.

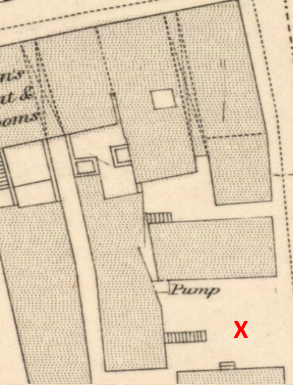

This is site of the Shaw bakery as it is today, marked on the picture by a pale square and a red X.

John Sanders the confectioner and Ann Vallance the grocer are both buried in the Abbey graveyard. John Sanders gravestone in the picture is the large flat one with two low markers at the head. Quite a number of grave plots were initially marked with a modest low marker, with a more prestigious gravestone added later.

Ann Vallance’s plot only has a very plain low marker. Before photographing it I scraped some of the moss off it to make sure it was the right one. Moss should only be removed if it is really necessary because it helps to protect the stone from weathering. but if you really need to do it a plastic card is useful because most people carry a number of them and it does not harm the stone. Just do not use a current credit card or one that really matters because it will be wrecked.

By 1851 the Shaws had four children living, but two babies had died – think how many Victorian women had to face that tragedy and the toughness they needed to carry on under that burden of grief. And that was not the end of it for Isabella. In November 1854 she gave birth to a son, Alexander, who died the following June of a brain disease.

Worse was to follow. At 4.45 in the morning of 14 May 1856 Alexander Shaw died of bronchitis and at 2.00 in the afternoon of the same day his last child was born, a daughter who Isabella named Alexandrina. She died of scarlet fever in the April of the following year.

Many years later her son Thomas wrote about his mother at this time;

No room in this world….can stamp its picture into my mind so deeply as the little reading parlour with the high glazed bookcase and the great leathern arm-chair in which of an evening she sat. So brave and practical she was. “In her tongue is the law of kindness”. Yet she was austere and with a high authority. Dimly I understood that she was seeing again the procession of her sorrows. And what sorrows they were! My father’s death, just as he was making his standing sure, then the infant girl born on the day of my father’s death and named after him, Alexandrina – she too torn from her arms. I remember the doctor coming and after his verdict….never in my life did I hear anything more pitiful than her heart-broken cry. Yet the dark clouds lifted, scattered by the stirrings of necessity.

Some necessity! After Alexander’s death Isabella had six children to support, aged from 15 to the new-born Alexandrina. She would have been helped by her brother Thomas, who lived in Chalmers Street and registered the deaths of both Alexander and Alexandrina, but she could not rely totally on him so she resorted to the remedy of many widows by carrying on her husband’s business.

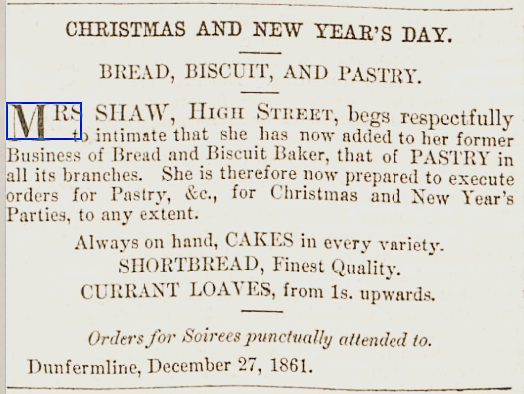

Isabella’s bakery did very well. Here is her advertisement in the Dunfermline Press for December 1861 informing the Town that she now supplied pastry goods, having probably hired a baker with the necessary skills.

Things went well until Mrs Vallance’s son Hugh took over his mother’s property and this map will help to explain what happened next. Hugh Vallance began to claim ownership of the close between his and Isabella’s properties and tried to prevent her from locking the gate to the High Street at night as she had always done. Isabella Shaw was not going to take this lying down and in January 1866 she brought an action against Hugh in the Sheriff Court, which ruled that the close belonged to her and that Hugh only had a right to use the close on the west side of his property.

Later in 1866 Isabella bought a basket maker’s shop in Guildhall Street which had an open area attached to it – marked with the red cross on the plan.. Some years previously the Dunfermline Police Commissioners had installed a public urinal in this place and in September Isabella employed the solicitor Alexander Macbeth to apply to the Commissioners to either have the urinal removed or to compensate her for the damage done to her property.

At first the Commissioners claimed that the area was public property, but Alexander Macbeth produced Isabella’s deeds, showing clearly that it belonged to her, so the Commissioners had to back down and this put them in a dilemma. They claimed quite rightly that while the urinal might be a ‘nuisance’ its existence helped to prevent the much worse ‘nuisance’ of the contamination of streets and closes. They asked Mr Macbeth how much compensation Isabella would accept, but she had hardened her stance and was now insisting on its complete removal.

The urinal was finally removed at the end of 1868, and was replaced by a public WC placed under the steps to the Music Hall.

By 1875 Isabella had retired, sold her shop to John Sanders the confectioner and moved to Edinburgh, where she lived on income from property, an annuity and dividends on shares. She died in 1884 at Eyre Crescent in Edinburgh.

She had apprenticed her son Thomas to a local solicitor and from that beginning he rose to become an advocate, then an MP and was finally ennobled as Lord Shaw of Carmyle. His autobiography, called Letters to Isobel can be downloaded from the archive.org website

Rags to Respectability

This story begins with a search for the last pauper burial in the graveyard. In 1863 the Halbeath Road Cemetery was opened and from that time onward all the free burials were in a section of the new Cemetery, but there was one last one in the Abbey Graveyard in February 1864.

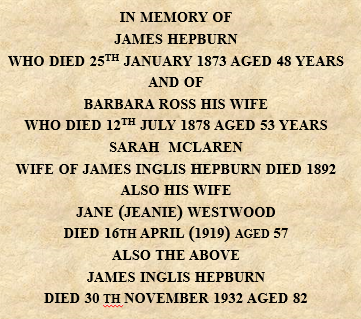

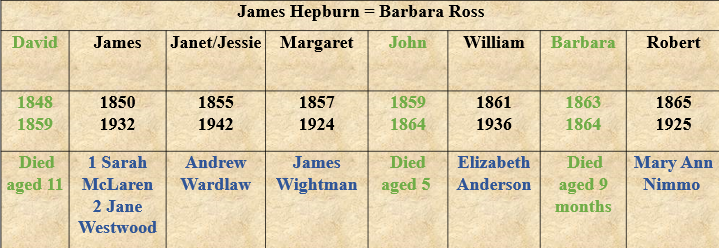

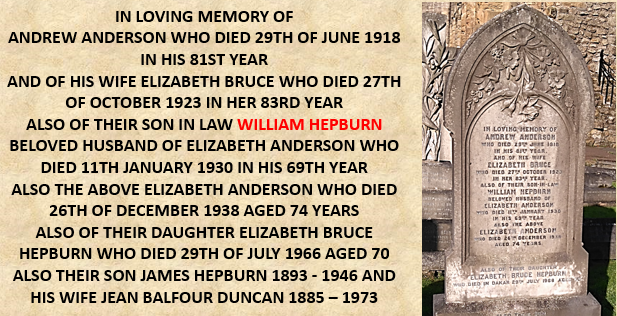

It was of a 9-month-old baby called Barbara Hepburn who died of diarrhoea and was buried in a free area of the graveyard, possibly because her brother David had been buried nearby in 1859. The inscription above is from her parents’ gravestone in the Halbeath Road Cemetery which was put up much later by one of their descendants.

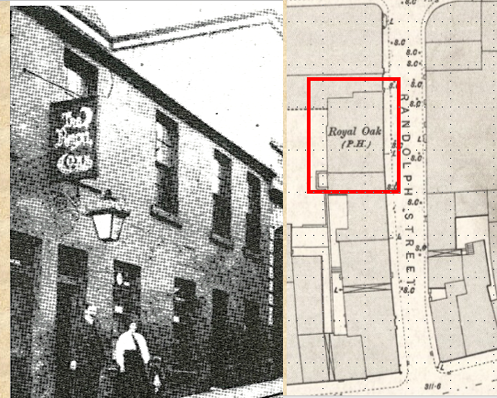

Perhaps it is a bit unfair to use the word ‘Rags’ in the title of this section because the family was not totally indigent. Barbara’s father James Hepburn was a joiner who also ran a pub in Randolph Street, the site of the Co-op buildings that have now been demolished, leaving a pleasant green space on the north side of the High Street. The picture shows the pub in later years, when it had been named the Royal Oak, and the map shows its position in Randolph Street

The family may not have been literally in rags, but they were certainly too poor to buy a burial plot. Perhaps a clue to their poverty may be found in the fact that when James Hepburn died in January 1873 he was suffering from liver disease.

Things looked up when James’ widow Barbara Ross took over the business. Within 18 months she had lent £300 on a mortgage on a property in the Netherton. Two and a half years later she lent £250 on a mortgage on the same property and in May 1875 £170 on a property in Beveridgewell. She died July 1868 and her eldest son, James, a clerk in a lawyer’s office, took over the pub, and it was James who named it ‘The Royal Oak’. (James was the James Inglis Hepburn of the gravestone inscription.)

The youngest son, Robert, was apprenticed to his uncle, James Alston, who ran a grocery shop in Pilmuir Street. Uncle James took Robert fully under his wing and left the business to him in his will.

Here is a family plan – the names coloured green are the children who died young and the blue ones are the spouses of the ones who survived to adulthood. There were two girls, Jessie who married Andrew Wardlaw, a painter and decorator, in 1879 and Maggie, who helped in Uncle James’ shop until she married James Wightman in 1882. Her husband was a joiner and his brother Henry was a partner in the furniture firm of Wilson and Wightman. So all the surviving family did well, but it is the middle son, William, who I want to concentrate on here.

William was 17 years old when his mother died and was working as a pupil teacher at the recently opened Pittencrieff School – the picture is of the school as it looked at the time. In 1880 William enrolled at the teacher training college in Edinburgh, living in lodgings in Picardy Place. After college he worked for a short time in Dumfries and Glasgow but by 1883 he was back at Pittencrieff School as a qualified assistant teacher and was also teaching evening classes in shorthand at the High School. He lived for a while in Golfdrum with his sister Maggie and her husband James Wightman and in 1891 he joined the Dewar Street Bowling Club.

In 1892 William married another schoolteacher, Elizabeth Anderson, daughter of Andrew Anderson who was the manager of the Canmore Linen Works. Their son James was born in 1894 and their daughter Eliza in 1897.

In 1898 William was appointed headmaster of Milesmark School and in 1900 his son Andrew was born. In that same year he applied to the Dean of Guild Court for a warrant to build a cottage (picture above) at the west end of Dewar Street on the corner with William Street, and the family moved there once the cottage was finished.

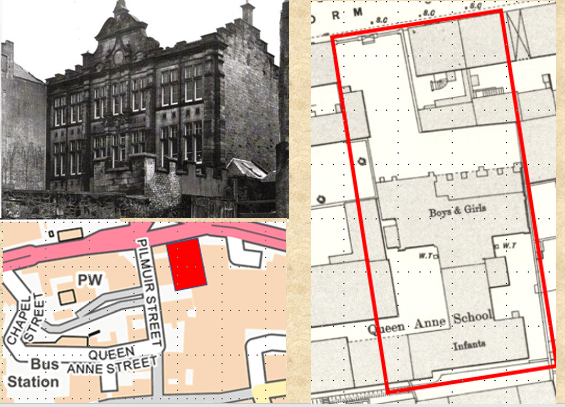

In 1908 William took a step up the promotion ladder when he was appointed Headmaster of Queen Anne School, in its first building in Reform St (now Carnegie Drive). At top left is a photograph of the school frontage. Below the photograph is a modern plan showing the location of the site. On the right is a section of an OS map showing the layout of the building and playgrounds, which stretched back to the northern boundary of the grounds of the Erskine Church.

In William Hepburn’s time the school had about 660 pupils aged from 5 to 13, which was the school leaving age for most children. Some of the brighter ones whose parents could afford to support them for a few more years, went on to the High School.

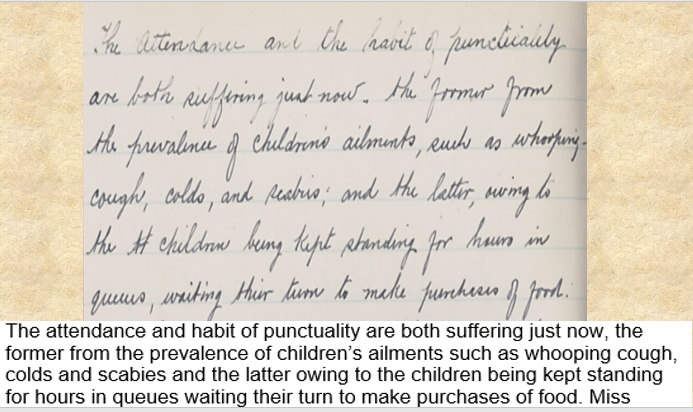

In January 1918 William returned to Pittencrieff school as headmaster and here is an entry from the school logbook that he wrote up every week. The logbook does not say much about WWI, which was still going on, but this entry for 15 February 1918 mentions one aspect of life at the time that is often forgotten. By the end of the war the food situation was desperate and food queues were many and long. Other school logbooks of the time also mention children being kept away from school to help queue for food for their families. This experience of food shortage was one reason why rationing started so early in WW2.

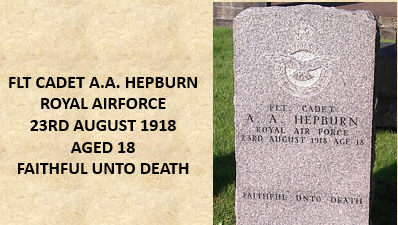

Any joy William might have felt at returning to his old school in January 1918 was short-lived because in the following August his son Andrew, who was training with the Air Force at Turnberry, was killed in a mid-air collision. His service record says his body was not found, but the Abbey burial register records that he was buried in the graveyard and this is his gravestone – a War Graves Commission design. His father recorded in his school logbook that on 26 August 1918:

The Headmaster was absent attending the funeral of his son, Flight Cadet A.A. Hepburn R.A.F, who was killed in an aeroplane accident at Turnberry on the 23rd inst.

On a happier note, the logbook records that on 11 November 1918

At 12.30 the children were assembled in the hall and told the glad news that the Armistice had been signed by Germany. Hearty cheers were given and the National Anthem was sung.

In February 1926 William reached the age of 65 and retired from Pittencrieff School and four years later he died of heart disease and bronchitis at his house in Dewar Street.

William was buried in his father-in-law’s plot in the graveyard and next to this gravestone is the headstone of his son Andrew. The part of the graveyard where William was buried was known as the Outshot – the section at the east end of the Fratery, which had been laid out as grave plots in 1900 – and William’s small brother and sister had been buried there all those years before. He must have known where he would eventually be buried and I wonder whether he ever thought about the coincidence that it would be in the same area where his little brother and sister also rested.

Conclusion

So there are half a dozen life-stories of Dunfermline people of the past. Some of them, like Barbara Stewart, David Dewar and Williamson Shoolbred had status in their day but for very different reasons. Granny Wallet had no status, but she was remembered with affection by those who met her as children and her death merited an article in thelocal Press. Isabella Shaw and William Hepburn lived lives that on the surface were not so very remarkable, but dig a bit deeper and you find qualities that brought them both through hard times to success in life.

There are many other stories to be told and there are plans for a More Tales From the Tombs talk at the Library in April 2020

Sources

Websites

‘Ancestry’, ‘Scotland’s People’, ‘The British Newspaper Archive’

Local Studies Library

Minutes of the meetings of the Dunfermline Commissioners of Police

(9 volumes 1837 – 1900. Indexed so far, 1837 – 1874)

Downloads from archive.org website

Reminiscences of Dunfermline

Letters to Isabel

(This website hosts a number of other downloadable books about Dunfermline’s history)

Private source

The deeds of the former Dunfermline Registry Office, Abbot Street.

Gravestone pictures and inscriptions

Dunfermline Abbey Graveyard Survey 2013 – 2016.

(Databases available on the Graveyard section of the dunfermlineheritage.org website)

With thanks to Sue Mowat.